(Originally posted October 28 2009)

“There is only one free lunch in investing, and this is asset allocation….Over time, it consistently leads to higher returns and lower risk.” (“Krawcheck stakes her new claim”

This blog should be read in conjunction with the Asset Allocation blog under the Education tab of this website. The objective here is to take a fresh look at asset allocation, and help the reader understand the moving parts that go into an asset allocation decision and perhaps allow her to apply to personal context. The key areas to be tackled here are:

-Definition of asset class, asset allocation and the purpose of asset allocation.

-expert perspectives on asset allocation

– risk and required return considerations

-examples of current/recent asset allocations recommended for Canadian and American investors

– how you might go about constructing your custom asset allocation

Asset Class, Asset Allocation and its Purpose

“Asset allocation is the process of deciding how to distribute an investor’s wealth among different countries and asset classes for investment purposes. An asset class is comprised of securities that have similar characteristics, attributes, and risk/return relationships. A broad asset class, such as ‘bonds’, can be divided into smaller asset classes, such as Treasury bonds, corporate bonds, and high yield bonds.” (p. 35 of Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management” by Reilly and Brown).

The purpose of asset allocation is diversification to maximize the return for a given level of risk taken. Of course we can only determine a posteriori the return and the risk that was actually taken, but Krawcheck recently very eloquently echoed what is generally accepted in the investment world that “There is only one free lunch in investing, and this is asset allocation….Over time, it consistently leads to higher returns and lower risk.” (“Krawcheck stakes her new claim”).

Perspectives on Asset Classes and Asset Allocation

Please bear with me as we run through some perspectives on asset allocation, before we’ll put it all together with some model portfolios for Canadian and American investors. As you might expect there is no unanimity on what is the best approach, and that’s as it should be since not all investors have identical needs, expectations and emotional makeup.

David Darst in “The Art of Asset Allocation” identifies three asset super-categories: (1) capital assets (equities, fixed income, and real estate cash flow based valuation), (2) consumable or tradable assets (energy, grains, base metals and livestock- supply and demand driven valuations), (3) store of value (art, antiques,

currencies, precious metals, jewelry- investor psychology/preference driven valuation)

Richard Ennis in “Parsimonious Asset Allocation” (FAJ 2009) argues that there has been a tendency for “category proliferation”, “ambiguity of categories (fuzzier)”, and a reduction in fixed income allocation in the expectation (or perhaps triumph of hope over reality) that correlations (or lack thereof) can be used to manage risk (when in fact “asset class return correlations are (really) unstable”, i.e. can’t use past data to reliably predict future correlations). Ennis suggests that investors are looking for three things: (1) downside protection (use “nominal and real-pay U.S. Treasuries of varying maturities”), (2) capture equity risk premium (use “a global stock index fund”), and if possible (3) some alpha or excess return(use “most compelling opportunities available to the investor for exploiting market inefficiency and capturing liquidity premiums”, i.e. it’s all about locating investment opportunities”). By the way, Ennis thinks of the “alternative” asset class as “miscellaneous” which typically includes commodities, hedge funds, private equity; as to “real assets” (real estate, commodities) he says that empirical evidence to support the inflation protection fame of these assets is weak.

Paul Samuelson in “Canny portfolios” (CFA Magazine, 2008) writes that “to a first approximation, all of us-young or old– living in the United States or in a European Union member state or Japan- could aim for the same passive diversified-index portfolio”. And, “when you reach 50, faced then with fewer investment periods ahead before retirement, you should transform holdings into safer stuff. “ (I can only guess, but given that he is referring to all those living in developed countries, perhaps he is talking about a based on a developed world capitalization weighted balanced portfolio.

Charles Ellis in “Winning the Loser’s Game” (a wonderful book you should read) writes “One of the core concepts and basic themes of this book is that funds available for long-term investment will do best for the investor if they are invested in stocks and kept in stock over time.” (He defines long-term as 10 years.)

An oft quoted Brinson, Hood and Beebower (1986) study showed that asset allocation explained 90% of quarterly variation between portfolios; and “Although investment strategy ( timing and stock selection) can result in significant returns, these are dwarfed by the return contribution from investment policy—the selection of asset classes and their normal weights.” In a follow-up study by Ibbotson and Kaplan (AIMR 2000), they “sought to answer the question: What part of the fund performance is explained by asset allocation policy?” Their conclusion was that “asset allocation explains about 90% of the variability of a fund’s return over time but explains only about 40% of the variation of returns among funds (“the remaining 60% is explained by other factors, such as asset-class timing, style within asset classes, security selection, and fees”). Furthermore, on average across funds, asset allocation policy explains a little more than 100% of the level of returns. As to the comment about the “remaining 60%” (explainable a posteriori by timing, style, security selection and fees) only lower fees can controllably/predictably enhance performance.

Jonathan Clements’s take in Main Street Money- 21 Simple truths that Help Real People Make Real Money(another great book that you should read) gives the following guidance on (a) asset classes, (b) asset allocation and application to one’s (c) portfolio::

(a) Assets classes – he suggests there are four classes: (1) stocks, (2) bonds, (3) cash and (4) hard assets(gold, commodities, real estate…). Returns for stock is (Inflation +7) %, bonds is (Inflation+2 to 3)%. Each separately has associated risk, but together the risk is somewhat reduced. Bonds/cash give downside protection, stocks help overcome corrosive effect of inflation and hard assets and TIPS give protection against inflation. As an aside, he mentions that you run the other way when you hear “downside protection with upside potential” as it usually ends up to be the worst of all worlds, low return and high cost. Real estate, hedge funds and private equity appear to give higher return and be more stable, but only because there is no daily pricing (and they are not as liquid)

(b) Asset allocation: divide your assets into ‘safe’ and ‘growth’ dollars, and make sure that the ‘safe’ pot is in safe assets. Allocation (among the four types of assets) drives risk (volatility) and returns. Stock/bond mix is determined by “how much risk can you reasonably take and how much you can truly stomach” (i.e. ability to take risk + willingness to take risk= overall risk tolerance). Stocks are an option only for portion of assets that you don’t expect to need for 7-8 years. Rebalance portfolio as different asset will be moving at different rates/direction but try to do it in a tax deferred account. Rebalancing doesn’t just mean sell something to buy something else; often you can achieve required balance by buying assets with interest and/or dividend received. Near retirement reduce stock allocation, but don’t abandon stock (inflation is corrosive).

(c) Portfolio: At one end of the spectrum his simple portfolio is 42% US total stock market, 18% foreign stock index and 40% US total bond market. His model for the elaborate portfolio (given on p.101) is 55% stocks, 10% hard assets and 35% bonds (1/3 TIPS) with suggested sub-allocations in each asset class. He argues that the exact percentages are less important than your willingness to stick with it (i.e. rebalance and don’t panic sell/buy), as it forces you to buy low and sell high!

David Swensen, CIO of the Yale endowment fund, in his PBS interview Consuela Mack’s May 22, 2009 interview of David Swensen on PBS expounded on his view of individual investors’ asset allocation. Well worth the half hour of your time to watch/listen to Swensen’s clear thinking and articulate communication about what individual investors should do. A few of his key points (and there were more): (1) his intent in writing his new(ish) book “Unconventional Success” was to translate the Yale model (which took a bruising 25% loss last year) to individuals and concluded that it was impossible; his conclusion is that you must be at either one end of the continuum (very active) or the other (completely passive), and an individual cannot be at the very active end, (2) recommended individual asset allocation in his book (I suspect for an investor with average risk tolerance) is 30% US stocks, 15% Treasuries, 15% TIPS, 15% REITs, 15% foreign developed country stocks and 10% emerging market equities, (3) given current fiscal and monetary stimulus, inflation is a high probability outcome, so every portfolio should have TIPS, in fact if you buy newly issued TIPS you also get protection against deflation.

In “Foundation and Endowment Investing” Kochard and Ritteriser, in their look in the context of the institutional/endowment world, write that -Asset Classes are: (1) U.S. public equity, for long-term hedge against inflation (though poor short-term performance when unexpected flare-up of inflation) and equity risk premium, (2) Non-U.S. (international) public equity for performance and currency diversification, (3) Fixed income (intermediate and long-term) -investment grade for deflation protection , (4) Fixed income –non-investment grade for enhanced return (5) Cash as source of low risk for cash-flow needs, (6) Real assets as hedge against inflation (real estate, real return bonds, commodities, timber/farmland), (7) Private equity for higher return than public equity (430 bp liquidity premium over public) and (8) Absolute returns for (hopefully) lower volatility (arbitrage, long-short, distressed, event-driven, etc). Emerging asset classes mentioned are: intellectual property, litigation finance, frontier emerging markets. And, -Rebalancing is critical- it helps you sell appreciated asset classes and buy ‘on sale’ ones. (But also keep in mind Swensen’s comments mentioned above, that that you must be at either one end of the continuum (very active) or the other (completely passive), and an individual cannot be at the very active end. Also don’t forget, that 2008 has was not kind to endowments/foundation portfolios.)

For some balance in views, I couldn’t leave out the dissenting (very conservative) stance of Russell Canada which was reported by Financial Post’s Jon Chevreau in “Two thirds fixed-income panacea for retirement security?”to be recommending near/in retirement a conservative approach of 65% bond allocation (within +/-5 years to minimize sequence of returns risk). Chevreau opined that this is too radical shift from the 35%-50% bond allocation in a traditional balanced portfolio, especially after a 50-60% drop in the markets from last year’s peaks. (Although there is a recent article by Rob Arnott who questions the future size of the equity risk premium commonly quoted at 4-5 %, shifting from a stock-heavy to a bond-heavy portfolio after the market dropped 50% seems a little like closing the barn-door after the horses departed; unless of course we are entering a world of a “new normal” as some have recently suggested.)

Marko Dimitrijevic in the Financial Times’ writes that “Emerging market label is obsolete”. “Emerging markets represent half of the world’s economy; their financial markets are large and liquid with volatility, corporate governance and government policies very similar to developed markets; (you might note that this is a result of not just improvements in developing countries but changes in perceived quality of developed markets’ governance). These traditional distinctions between emerging and developed markets, once pronounced, have disappeared.” Developed markets have recently demonstrated that that they can suffer from “poor corporate governance and less market-friendly government policies” just like emerging markets. Emerging market growth rates have significantly exceeded those of developed countries and “differential in growth will continue for three key reasons: the differentials in GDP and population growth will be maintained for the foreseeable future; many emerging markets’ basic needs have not yet been met, so starting from a lower base, consumption and investments will continue to grow faster; and from a risk standpoint, their companies were and continue to be less leveraged, with higher interest coverage ratios than those in developed markets.” Most importantly emerging markets “represent only 12 per cent of the MSCI All Country World Index, while representing 30 per cent of the world’s market capitalization, 50 per cent of the world’s economy, and the world’s best growth prospects. Investors focusing on benchmarks will miss this opportunity.” (This is a not a new argument and, for some, it could be a strong argument for increasing the MSCI capitalization weighted index based 13% allocation to emerging markets. But in Financial Times’ “Question of maturity in developing markets”John Authers raises some cautionary flags given the enthusiasm associated with emerging markets. He warns that while “the economic data for the emerging markets seemed to justify the enthusiasm”; some of the reasons for investing in emerging markets (cheap compared to developed markets and providing uncorrelated returns) are more questionable today. (You’ll have to make your own call to overweight or not emerging markets; personally I’ve been inclined to overweight within the envelope of my risky assets.)

Life-cycle investing broadens the way you look at asset allocation. It looks at an individual’s ‘Total Capital’ (TC) as being composed of the sum of ‘Human Capital’ (HC) and ‘Financial Capital’ (FC) i.e. TC=HC+FC. When one starts working, one’s capital is essentially HC, whereas once one has retired one’s capital is essentially (close to) 100% FC. So the large proportion of HC for a young person (which is typically, though not necessarily, bond-like), in effect allows a significant portion of the FC to be allocated to risky assets (equities); whereas for an individual approaching retirement, HC is gradually approaching zero so one has to be more careful with FC resulting in a much higher proportion of low-risk fixed income asset allocation. Human Capital (HC) is calculated by discounting the lifetime cash-flow associated with the individual’s labour, and the discount rate may be determined by the profession that an individual is in. A government employee’s income may be discounted by something not far from say high quality corporate bonds, while a hedge fund manager’s income, being much more precarious (and highly correlated with the market) would be discounted at much higher rate. It’s not uncommon to find hedge fund managers’ personal portfolio primarily invested in risk-free assets. Life-cycle investing will be expanded on in a future blog; some of the early work on this was already touched upon in a Life-Cycle Investingblog

Among other approaches to asset allocation and risk control are: the old standby of allocating to stock a percentage of (100-age), target-date “glide-path”, Bodie’s 90%+ in Treasuries and the rest in options to try to protect the downside but capture some of the upside of the markets, core-satellite (do the “standard” asset allocation in the portfolio ‘core’ (80-90%) and the use the remaining 10-20% to for special opportunities), asset allocations driven by certain level of target withdrawals of say 3, 5 or 7%, or dynamic asset allocation approaches (e.g. Constant Proportion Portfolio Insurance (CPPI) for risk management).

Risk and Asset Allocation

John Authers writes in the Financial Times that “Crisis creates new sophistication in risk”.Correlation based approaches to risk failed to protect the downside in the recent crash, when suddenly everything became correlated. Some other approaches being tabled now are: (1) “risk factor” rather than asset class based (risk factors such as-not just the classical equity, default, interest rates, inflation, liquidity, but also public policy), (2) “risk of outright loss, rather than the volatility of returns” (look at 9 types of risk: concentration (‘fad’ investing), leverage, liquidity, transparency, sensitivity to overall equity and bond markets, event, volatility, and operational risk.) He argues that the move to passive approach will continue and relative performance will be of lesser concern than absolute returns.

Hyman Minsky’s view was that “financial systems are inherently susceptible to destructive bouts of speculation. During these periods of apparent tranquility, Gaussian models …downplay the probability of an outlying event…According to Minsky, stability is destabilizing because stability leads investors to extrapolate stability into the distant future; therefore the more stability the market exhibits and the longer it lasts, the more unstable the foundation of the stability becomes”. (Steven Mauzy, “Risk runs roughshod”, CFA Magazine, 2008)

So while there is a considerable opinion (and data) in support of asset allocation as a means of risk control, last year’s crash has re-opened arguments about the effectiveness of asset allocation based on historical correlations (especially at times of market stress).

In preparing an Investment Policy Statement (IPS) risk tolerance of an individual sets the maximum limit on the portfolio risk, while required return sets the lower bound of portfolio risk. Hopefully, required return driven risk doesn’t exceed risk tolerance; if it does, the objective must be reduced to a more modest level, and/or savings level must increased further to achieve objectives.) Many will also advocate that one shouldn’t take more risk that one needs to in order to achieve one’s objectives, even if one’s risk tolerance would allow more risk! So this (IPS) is one of the areas that a good “advisor” actually earns his fee; if your advisor didn’t generate an IPS, you might want to ask yourself (and the advisor) what in fact you are getting for your fees.

Risk tolerance is a combination of ability to accept/take risk (i.e. a function of the circumstances of an individual investor, one’s asset sourced cash flow requirements over next 2, 5 or 10 years, or perspectives like younger person can take more risk since she has many more years to recover given remaining earning power and its sustainability) and willingness to take risk(i.e. how much loss is an investor prepared to take a day/month/year and still sleep at night, and not abandon the stock market altogether). When there is a significant gap between one’s ability and willingness to take risk, it is essential to get educated and try to close that gap. The risk tolerance drives one’s allocation to risky and risk-free assets and is a primary determinant of asset allocation.

In the strictest sense, just about everything except domestic T-bills or government bonds maturing when cash is needed can be considered risky. Local currency (domestic) government bonds are usually risk-free; Canadian government bonds for Canadians, assuming that their spending is in Canadian dollars, have no currency risk; maturing when the cash is needed means that there is no interest rate risk. Corporate bonds would have credit risk, foreign currency bonds would also add currency (and other types of) risk. Equities are also risky. But generally, risk and return tend to go hand in hand, so those who want or need higher return would have to accept higher risk. (Of course, unless the investor buys inflation indexed or real return bonds, she is still exposed to inflation risk.)

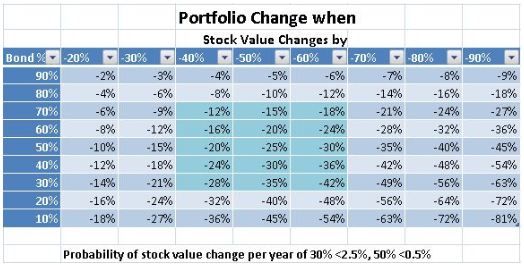

The following simple table gives you the portfolio change (decrease) in value given a particular asset allocation and a percent drop in stock market value (say per year). So (for your willingness to take risk) if the maximum portfolio loss that you are willing to tolerate is 20% and you figure that the maximum loss in the stock market might be 40%-50% then you portfolio should be 50-60% in bonds (see table below). Assuming a Gaussian distribution (the world doesn’t always behave that way as we recently found out) for annual stock market returns with an expected return of 10% and standard deviation of 20%, then there is about a 2.5 % probability of having a loss > 30% and <.5% probability of losses >50% in a year (expected return less2x or 3x the standard deviation; i.e. 10-2×20=-30% and 10-3×20=-50%). By this statistical assumption, last year was an exceptional year (or more likely perhaps the assumed distribution does not fully describe the likely outcomes). So, one would have to look at some worst case scenarios in addition to relying on the Gaussian distribution. And this table gives you a simple way of assess your willingness to take risk making some worst case assumption on annual or tri-annual stock market loss and looking at your assumed portfolio bond content.

How much risk do you need to take? Required rate of return?

For a very wealthy investor (and the way to think about wealthy is one whose annual spending needs from his assets are very small compared to his assets), one may be able to invest all the assets in (inflation indexed) government bonds and just live on the income. This person’s assets (bond principal) and income (interest) would grow with inflation.

For those of us whose spending requirements cannot be satisfied with interest from inflation indexed bonds alone, we will have to either reduce our spending or add some asset classes which have higher expected returns. Combining higher return (and higher risk) assets may lead to higher expected total return which on the average may meet spending requirements of the investor, but investor will have to live with uncertainty of returns in any one year. The point here is that one should not take more risk than necessary to meet one’s objectives (be they life-style needs and/or desire to leave an estate.) This is especially true near retirement, when one may still have income requirements for 30+ years (e.g. to age 95).

Some of the historical returns associated with different asset classes are as follows (I=inflation):

-government bonds= I + 2%; (real return bonds= 2-2.5%, though currently lower)

-corporate bonds = I + 3%

-stocks (total return) = I + 7.5% (equity risk premium of about 4.5%)

Therefore, based on historical returns, a balanced portfolio (50% stock and 50% bonds) would return (I + 5%). For planning purposes, given that there is some question of whether historical equity returns can in fact be maintained going forward, we might use a somewhat more conservative (I+ 4%); i.e. a real return of 4%. Using a more aggressive asset mix of 70% instead of 50% equities, we would gain another 1% expected return, but at a significantly increased level of risk. I would not suggest such an aggressive portfolio for anyone within 7-10 years of or in retirement.

A Sectoral/Industry View of Asset Allocation and Risk

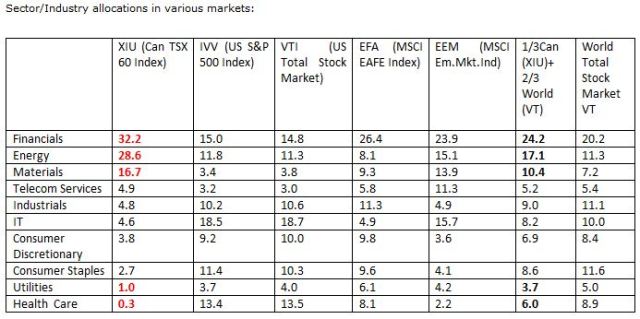

One might want look at a sectoral view of allocation to determine if one’s portfolio has an over-concentration in a particular sector. It is actually interesting to look at different market indexes and note that the Canadian market is relatively undiversified with its very heavy allocation to financials (32%) and commodities (45% including energy and materials) and almost no exposure to other sectors like healthcare and utilities; so for those Canadians invested exclusively in an ETF (index) representing the Canadian market, they end up with a not a very well diversified investment. The US, EAFE and even emerging markets are less sensitive to financials and commodities and give you 8-13% exposure to healthcare. A 1/3 Canadian and 2/3 World stock market (second to last column in table below) provides a better sectoral diversification by reducing concentration to financials and commodities to a more reasonable 24% and 27%, and increases healthcare to 6%; It also adds currency and geographical diversification. Note that for a 50% bond portfolio where the fixed income portion is all in Canadian currency, when 1/3 of the equity exposure is Canadian, the overall Canadian currency exposure is (a not unreasonable) 67%.

Sector/Industry allocations in various markets:

Another test for level of diversification of a portfolio might be to consider geographical/currency diversification. On the currency front one might want to factor in the currency that one is planning to do the spending from the portfolio (i.e. one’s liabilities). For Canadian the 1/3 domestic and 2/3 foreign also provides good geographic and currency (if unhedged) diversification.

Examples of recommended Asset Allocations

The first five columns in the following table give some asset allocation examples for U.S. Investors. No doubt that the Swensen and Clements columns show 0 (zero) cash, purely because they assume that the cash reserves required for individuals are dealt with separately. The last two columns are based on the same young individual’s circumstances; the last column is based on her ability to take risk (i.e. once the known cash requirements are covered the rest of the assets are invested in risky assets, whereas the second to last column factors in a (more conservative) willingness to take risk criterion which drives 11% of assets into the fixed income beyond the cash requirements. (If the gap cannot be resolved between willingness and ability to take risk, you’d have to proceed with more conservative allocation based on willingness.)Note that these last two columns have 10% allocated to alternative asset class (gold and commodities in this case) and the equity portion uses 39%, 43% and a (higher) 18% (than dictated by the MSCI global cap-based 41%, 46% and 13%) allocation for U.S., EAFE+Canada, and Emerging Markets, respectively. (By the way Canada represents about 3.6% of global equity market cap.)

The following table is aimed at Canadian Investors and it includes not just Canadian examples, but also some of the U.S. references as well. Note that I have included my portfolio it has an 11% alternative asset allocation (gold and hedge funds), and the stock/equity strategic allocation is 31%, 25%, 25% and (not 13% but) 19% in Canadian, U.S., EAFE and Emerging Markets, respectively. (This is approximately 1/3 Canadian and 2/3 rest of the world mix mentioned previously in the sectoral allocation discussion. Also, my (tactical) cash allocation is heavier than usual due to high uncertainty associated with my Nortel pension outcome and unusual uncertainty in the markets.)

Now putting it altogether

So in the simplest terms we can think of only two asset classes: a risk-free one (domestic T-bills) and a risky asset class (everything else, each of different levels of risk and correlations). So let’s start to build a simple portfolio.

The primary purpose of our assets is meeting our future needs/spending-requirements. So when we are young and working, we must start off with a reserve fund which can cover our short-term expenses in case we lose our job. Depending on the job market and one’s marketability, you might want to have a reserve to cover 3-24 months of spending requirements. It is advisable to also include any known major outlays over next five years or so (e.g. mortgage related down payment.)

The next layer of need is risk tolerance related. First the ability to take risk is associated with known/planned cash-requirements over the next 2 to 10 years; these requirements could be protected by a series risk-free (or low-risk) cash-flows like GIC/CD/bonds selected to mature when the cash is needed. For a young person the typical needs may be down payment for a house or buying a car/roof, whereas for a retired individual it would be the income requirements from assets in excess of those covered by CPP/OAS or Social Security and other DB pension sources. (The undiscounted 10 year requirements of a retiree, assuming 4% annual withdrawal from a balanced portfolio, would be about 40%; this would suggest that such a retiree’s ability to take risk might result in an asset allocation to equity up to 60 %.) The other consideration in determining the proportion of risk-free (low-risk) assets would be the assessment for the individual’s willingness to take risk(i.e. accept losses). If the maximum acceptable portfolio loss per year might be 15% and over a 3 year period might be 35%; then assuming worst-case stock (equity) losses of say 40%/yr and 70% over 3 yrs the respective risk-free (‘bond’) allocations required would be at least 62.5% and 50%, respectively. (You can plug in your own worst-case stock loss scenarios for one and three years into the portfolio change matrix above.)

The remaining assets can be invested in risky assets which will hopefully give us the required expected portfolio return in the long-term to try to cope with inflation.

Bottom Line

For the simplest approach:

(1) risk-free (low-risk, fixed-income) allocation driven by:

-required cash reserves for 3-24 months

-maximum of cash-flow needs from assets (to cover needs up to 10 years, driven by risk-tolerance)

(2) any assets not expected to be required in the following ten years, consistent with our risk-tolerance may be invested in risky equity-like assets

The three asset classes that we’ll use are cash, risk-free, equity.

These could be implemented very simply as:

(a) cash= domestic T-bills or cashable CD/GIC (recently I have also used XSB the Barclays Short Term Bond ETF to get a little higher interest, but it has a duration of 2.6 so a 1% increase in interest rates would reduce the value of the bonds by 2.6%, wiping out a whole year’s worth of interest.) Americans of course would want to look at tax-exempt municipal and state money market funds if not in a tax-deferred account.

(b) risk-free= compound domestic GICs/CDs maturing to corresponding with the timing and value of expected cash out-flow requirements (I also hold provincial strips in my RRSP, but more recently I‘ve bought GIC since provincial bonds became quite expensive.) Ideally, interest bearing securities should be held in tax-deferred accounts to minimize taxes.

(c) equity= the classical text-book recommendation for what is “optimal” is to have capitalization weighted exposure to the world stock market, however investors (for good reasons) have home biases and it’s not uncommon to find Americans and Canadians 100% invested in their respective home markets, even though they only represents about 40% and 4% respectively of the world stock market cap).

The simplest diversified approach for Americans would be to use 100% VT (Vanguard World Stock ETF) which still gives them 40%+ exposure to US markets, while for Canadians 1/3 XIU (iShares S&P TSX 60 Index) and 2/3 VT would result about 37% in Canadian markets. In addition, one might wish to make allowance for increasing importance of emerging markets (higher growth rates, higher weighting if done on PPP or GDP basis). Therefore instead of using the (a little more granularized ) capitalization weighted US, Canada, developed EAFE and Emerging Market allocations of 41%, 4%, 42% and 13%, Canadians might choose 25%, 31%, 25% and 19%; Americans might consider 39% U.S. 43% developed EAFE + Canada and 18% Emerging Markets. An ETF based portfolio could easily be constructed, you just have to pay attention to cost, liquidity (daily volume), and whether they are hedged (my inclination is to go unhedged for diversification, though some advocate fully hedged approach, so if you are concerned you could go half hedged and half unhedged.)

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention a couple of key tactical considerations that:

- an important contributor to return associated with a particular asset allocation is the periodic rebalancing (to force you to sell the expensive and buy the cheap assets.)

- while I am mostly a buy-and-hold type of person, it can be important, especially when a portfolio is being built ground-up, that portfolio additions and changes are made gradually; I am not advocating market timing but in building asset class positions one should keep in mind that buying expensive assets condemns us to lower returns, so in (re-)deploying larger sums of money one might want to do it in smaller chunks over time with an eye on price.

For those who insist on not keeping things simple, further refinement might be considered. Within the equity asset class in a particular market one might use equally weighted allocation (this would remove the large company bias), fundamentally weighted allocation (an approach giving higher weighting to value stocks compared to growth stocks). Others might also consider an extra dose of small company stocks, since many believe that they have higher return potential. In the bond asset class allocation some suggest adding foreign bonds, real return bonds and junk bonds, but you must keep in mind that the fixed income allocation is intended for protecting one’s (usually domestic) spending power so don’t go overboard with currency, credit and (nowadays) duration risk.